Oldfield Park Junior School (Bath) WW1 Memorial Project

Bath War Memorial

Few people who visit the Bath War Memorial today suspect that its history is any different than any other town or city’s War Memorial. It seems obvious that, following the huge sacrifices of WW1, each community should commemorate and honour its own dead. Most towns and cities seem to have been able to quickly decide on a plan for a central cenotaph and to find somewhere fitting for it to reside. Not so in Bath.

In 1919, as smaller communities – such as the villages around Bath and the individual parishes within it – formed plans to commemorate their war dead, the City of Bath realised that it, too, must act. A Chronicle columnist warned that so many individual parish schemes were being planned, that the importance of any future central Bath memorial was likely to be diminished if it was not done quickly. At an inaugural public meeting that year, held to discuss the nature of any public memorial, a vast array of different proposals was put forward. These included everything from a memorial garden, a winter garden and concert hall, paid-for beds at the RUH (in a wing that was itself a memorial for Prince Albert), an ex-servicemen's club and a library. There had never been such widespread commemoration of such a significant event and we must put ourselves in the shoes of those in public office who had to come to a decision on how best to unite and represent the common will to mark the huge losses of WW1.

There was an interesting moral debate at the time across many communities (not least in Bath and its individual parishes) as to whether a 'functional' memorial (such as a hall) was not more for the indulgence of the living than a commemoration of the dead. Some plans put forward as potential memorials were ideas for public amenities that pre-dated the war; the accusation in such cases was that people were abusing the notion of commemoration to get ‘pet projects’ completed. Gradually, public opinion tended to shift in most cases towards a plain memorial, to avoid any such accusations of self-serving. But several ‘utilitarian’ memorials were realised in Bath alongside those of stone and metal whose function is purely to remind.

When a special Committee was formed in Bath to address the issue of a War Memorial, it soon fell foul of political squabbling. There was dissatisfaction among Bath’s Trades Council that they might not be as strongly represented on the War Memorial Committee as they might have wished. For a time, they threatened to withdraw their participation in the scheme and erect a separate memorial of their own, focusing on the sacrifice of the working classes. The rift was, however, healed in time. It is interesting to note that the Secretary of the Trades Council at that time was H J Swain, father of Harold Swain. But there were stories of personal loss on all sides; the Mayor who served Bath during WW1, Harry Hatt, had lost two sons in the War and he, too, was on the Committee.

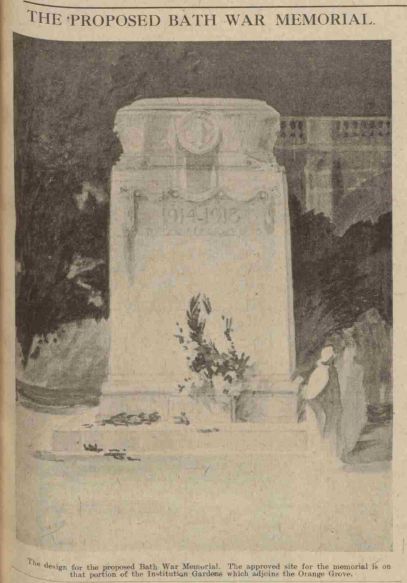

Once it was decided that Bath’s memorial would take the form of a cenotaph, the next issue was where it could be sited. The original site suggested in 1920 was at the junction of Stall Street and Bath Street. This would have caused the removal of the Pieroni fountain to the Cross Bath end of Bath Street. The Abbey Churchyard was also considered. Then, still in the same year, the site of the Institution Gardens steps (now known as Parade Gardens, where the Edward VII memorial is now) was suggested.

One of the issues affecting the Institution Gardens plan was that an entry fee was payable for the gardens, thus potentially limiting access. The Orange Grove was also suggested, but the committee didn’t think the cabstand (present at the time) would be a fitting neighbour for the memorial and the removal of the obelisk to the Prince of Orange would also be required. This obelisk had become part of an iconic view of Bath’s Abbey owing to a burgeoning postcard industry, and the Committee was loathe for their scheme to displace an existing memorial, lest a precedent be set, whereby their WW1 memorial could suffer the same fate at a later date. In the meantime, a ‘shilling fund’ was opened for public subscriptions, with an ‘appeal target’ of £3,000.

When Mr Swain asked whether any memorial would include the names of the fallen servicemen, the reply was in the negative; it was stated that the list could run to 5,000-6,000 names and that this would create problems of ‘making a selection’. In any case, the names would all be preserved in the ‘Golden Book’ in Wells Cathedral. A further query was whether the scheme could be progressed by making use of the labour of the growing number of the unemployed, in order to give them something to do. This was quickly dispelled as blurring the line between commemoration and pure utilitarian aims.

By Oct 1920 the fund had reached only £626. The Mayor let it be known that the fund would be ‘closed by Armistice Day’. In the end, nothing like the required amount of money had been raised and, indeed, there was not even an agreed scheme in place that people were contributing towards. At this stage, the whole process seems to have fizzled out, while the years 1920 and 1921 saw many local memorials erected and dedicated. When unveiling the War Memorial plaque at the City Secondary School in 1922, the Mayor (Alderman Cedric Chivers) publicly expressed his regret that Bath did not have a central memorial.

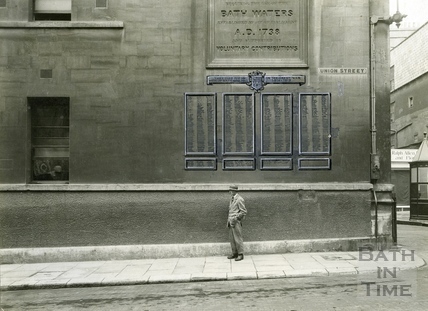

Indeed, it was Cedric Chivers who became the prime mover in the quest to put a city memorial in place. He had made a promise at the time of his 1922 election to ensure a memorial was erected. This he did without ado, without recourse to any committee and at his own expense. In April 1923, bronze plaques bearing the names of the fallen servicemen of WW1 were affixed to the side wall of the Mineral Water hospital. These were the gift of the Mayor, who proposed that the plaques should be adorned with fresh wreaths, to be replaced whenever necessary.

An artist's impression of the plaques ahead of their installation in Union Street, 1923 [Image: Bath In Time]

May 1923 saw the war memorial in Locksbrook cemetery unveiled in front of a crowd of thousands. It followed the ‘Cross of Sacrifice’ design in Portland stone and bronze, as designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield and used across the many cemeteries on the battlefields of WW1.

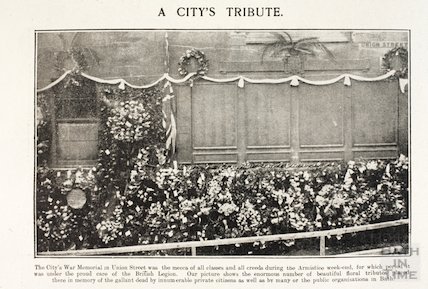

The Union Street tablets quickly became a focal point for remembrance. As well as public acts of remembrance on appointed occasions, there was at last a physical place for the many private tributes of the bereaved and sorrowing. More than one bride headed straight from the altar to the memorial in order to place her bouquet of flowers there; perhaps for a brother or for a lost love. Other individuals took to hanging glass jars with flowers from the pegs that were intended for wreaths; measures were taken to stop the practice.

In September 1923 the 2nd Battalion of the King’s Royal Rifles also paid tribute at the memorial as they took their leave after having been billeted in Bath.

In October 1923, with the plaques just months old, new tablets had to be added to cater for the additional names of fallen soldiers that had been put forward since the original installation. As an attempt at future-proofing, these new tablets had removeable sections that could be re-cast with names and re-inserted into the panels. Lights were also installed to allow the names to be read during the evening.

In November 1923 the Armistice Day parades to the Abbey were routed down Union Street and past the memorial. The North Somerset Yeomanry were first to halt their parade there in order to observe a silence and to leave a wreath. They were followed by the Salvation Army and the Wessex Royal Engineers.

By December 1923 the memorial had 14 more names added, bringing the total to 1057.

In February 1924, Major-General Bradshaw, President of the Bath Royal British Legion, remarked that the public were not showing sufficient reverence in the vicinity of the memorial. He suggested that people should not smoke as they passed and that heads should be uncovered. Major-General Bradshaw became an important name in connection with the War Memorial, however, as it was announced in November 1924 that a special committee of the Bath Royal British Legion was commencing a new initiative to address the issue of a permanent Memorial and that a new fund had been kicked off with anonymous donations amounting to £150. But things went quiet again. In the early part of 1925 there was an undertaking from Mr Joseph Elsom, florist of the city, to provide chaplets for the Union Street tablets and to renew these as often as necessary. In May the flags on the memorial were cleaned.

Against this backdrop, there was a growing sense of public disquiet about the lack of progress and the sheer silence from the new Committee. Letters and commentary began to appear in the Chronicle, sometimes signed by ex-servicemen, asking what was the state of affairs and bemoaning the interminable delay.

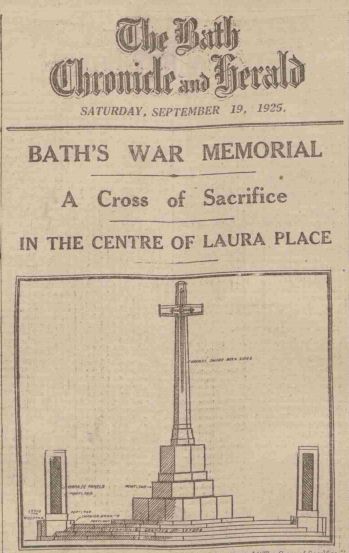

At last, in September 1925, there was a big announcement by the Royal British Legion under Chairman Bradshaw. A final decision had been reached: the memorial would take the form of a Cross of Sacrifice (Blomfield design) and an appropriate site had been found and agreed by all parties. The site? The centre of Laura Place.

At the public meeting where this announcement was made, there was unanimous support for the Laura Place scheme. It was estimated that the cost would be £2,000 and a new public subscription was opened.

It only took until the next Council meeting a few weeks later (October) for the mood to change and for the site in Laura Place to be considered less than ideal. The Council deferred approval and, without any definite plan in place, the inauguration of the new subscription fund was also deferred. The public discussions laid bare the profound issues of personal sentiment involved, exemplified by Harry Hatt’s loss of his two sons; he was on the British Legion committee as well as the Council. The Council then sought Sir Reginald Blomfield’s opinion on the setting; someone had suggested that Blomfield was known to prefer a backdrop of trees to the Cross of Sacrifice wherever possible.

The Trades Council supported the Laura Place scheme. In the dissection of the disagreement, the Honorary Secretary of the Trades Council (also a member of the special committee) stated that plans and photos of every other memorial in the country had been viewed, as had every available site ‘to the four corners of the city’. But as the 1920s were wearing on, there was also the sense that money might be better spent on the living – many of whom were out of work and hungry – rather than the dead. The memorial scheme was in jeopardy again.

This poem by F.E. Weatherly appeared in the local newspaper:

Why chide, if men have different dreams

Why scold, if men do not agree

When one clear light before us gleams

When one straight purpose all can see

So – whatsoe’er be done or said

Find some calm spot where we may pray

To do our duty, like the dead!

And sleep as peacefully as they!

Sir Reginald Blomfield was brought to Bath in November 1925 and he reviewed a number of alternative sites. The annual marking of Armistice Day took place much as it had done the previous year, with the North Somerset Yeomanry, Wessex Engineers, 4th Battalion Somerset LI, King Edward School OTC, British Legion St John Ambulance and Red Cross / Voluntary Aid Detachment all paying their respects in Union Street as part of proceedings. The year ended with a correspondent to the newspaper suggesting the summit of Twerton Roundhill as a site for a memorial, in order to use the effect of the setting sun. This was described by a columnist as ‘poetic but impolitic’.

So 1926 began with further pointed letters of protest in the Bath Chronicle & Herald and a lack of any update from the Committee.

Then, in March, the newspaper carried word from the Mayor that the site for the memorial was decided: it would be on the south side of Queen Square. This site had now been approved both by the Council and by Sir Reginald Blomfield himself. It had apparently taken a long time to make the proposal public owing to the fact that the Queen Square garden was owned jointly by the owners of the buildings that form the square [as it still is today].

It was proposed that a canvas mock-up of the memorial be put up in the square, in order to show interested parties how the memorial would fit in. It is not clear whether this ever happened. In the end, the Queen Square site did not meet with wholehearted approval either and things went quiet once more. It was June 1926 before plans were announced in the Chronicle to have the memorial sited at the entrance to Royal Victoria Park. It was hoped to have the memorial completed by the Armistice Day of that year and a scheduled November visit of the Prince of Wales could feasibly include an unveiling of the finished memorial by his Royal Highness. Again, £3,000 was the stated sum required, of which some had already accrued from previous appeals. By August the sum of £1279 had been raised. The Mayor suggested releasing postcards for sale bearing the poem by Mr. Weatherly as a means of fundraising. After a public tender process, the builders were announced as Chancellor’s and the bronze work was supplied by Singer’s of Frome.

Then the issue of names was raised again. A correspondent to the newspaper suggested that the bronze panels should be re-cast with all the names in alphabetical order; many names had been submitted and added, subsequent to the initial casting of the tablets, meaning that some names appeared almost as an afterthought. The Mayor stated that the re-casting would cost in excess of £1,000. As he was the one who had paid for the original panels from his own pocket, he did have the benefit of knowledge of the facts. The argument was also put that further names might subsequently be submitted, thereby rendering the re-castings obsolete in their turn.

As it was, work on the memorial site did not begin until November 1926. Armistice Day 1926 was marked as it had been in the immediately preceding years, with military units and civilians paying their respects at the tablets in Union Street.

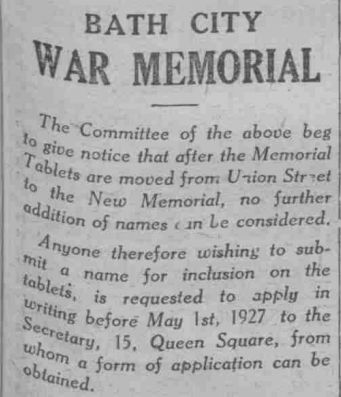

The £3,000 appeal total was reached in January 1927 and the Committee put out a notice that all names to be included on the memorial should be submitted by May of that year; it appeared that the work of re-casting the name plaques was indeed being incorporated in the scheme.

In February the deadline for name submissions was brought forward to March, owing to the amount of work incurred by the large number of submissions. Around 120 names were submitted, of which half were said to have been perfectly fine; the other half necessitated some checking of names and avoidance of duplicates etc. The unveiling was planned for May, but then deferred.

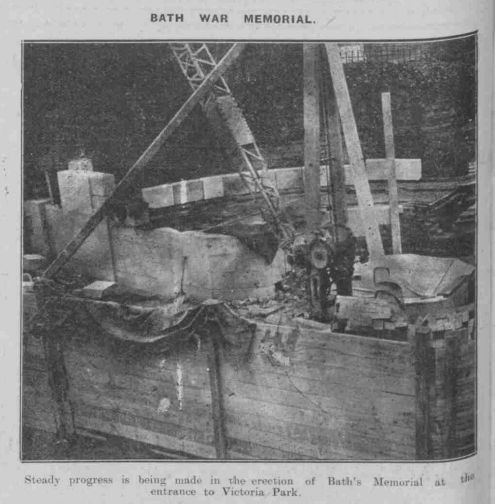

Progress in January 1927 (above) and April (below)

Over the summer it became an open secret that attempts were being made to arrange for the Duke of York (who later became George VI) to perform the unveiling ceremony, but in October it was learned that the Duke’s plans would not allow for this.

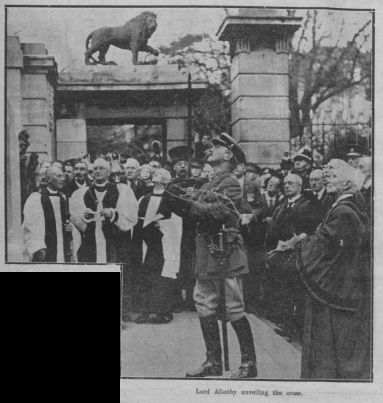

Instead the many years of waiting and debating were finally brought to an end on Thursday 3rd November 1927. The dignitary who performed the task was Lord Allenby.

Here is the article from the Bath Chronicle & Weekly Gazette from 5th November 1927: (abridged)

BATH'S WAR MEMORIAL

LORD ALLENBY’S RECEPTION

Inspects Troops and Attends Civic Luncheon

Lord Allenby, who arrived by the Spa Express at one o’clock was met at the station by Major G.D. Lock (Chairman of the War Memorial Committee) and proceeded in a motor-car to the Guildhall. A Guard of Honour of 50 men of the 4th Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry, under the command of Wilfred Lewis with Lieut. V.E. Rowse carrying the Regimental Colour was drawn up in High Street facing the main entrance to the Guildhall. The Regimental Band was in attendance. Lord Allenby was received with the General Salute. He proceeded to inspect the Guard of Honour. Most of those who composed it showed by the medals they wore the honourable part they had played in the Great War. Lord Allenby afterwards entered the Guildhall, where he, and a small party of other guests, were entertained to luncheon by the Mayor of Bath (Alderman Cedric Chivers) who, to the general regret, was unable to be present owing to his illness.

Ceremony of Deep Impressiveness

LORD ALLENBY'S ADDRESS

People's Tribute to the Gallant Dead

Bath has at last a great War Memorial. Already its stones have been trodden by the footsteps of thousands of the kith and kin of twelve hundred of the city’s sons who were faithful even unto death. For since its unveiling by Field Marshal Lord Allenby on Thursday afternoon a host of relatives have paid a pilgrimage to it, read in bronze the names of the imperishable dead, and many deposited a wreath or a few flowers as fragrant as the memories that Thursday’s solemn ceremony quickened as if they were only of yesterday. It is a great memorial of the dead. That Cross of Sacrifice, which rears its emblematic shape in many a Flanders field and in the further flung cemeteries where our sons repose, brings into our midst a symbol of their death, and has spiritual kinship with the holy place where they lie –

“On thee shall press no ponderous tomb;

But on thy turf shall roses rear

Their leaves the earliest of the year

And the wild cypress wave in tender gloom”

Here, at this revered shrine, in the elegance and durability of the stone and bronze, we may now and hereafter “lingering pause and lightly tread,” and, remembering, try in our feeble way to emulate their high example and to carry on the torch of humanity which slipped only from their grasp in death.

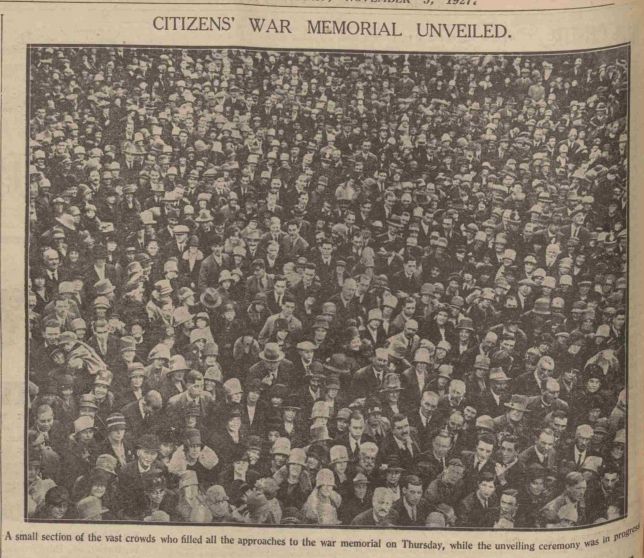

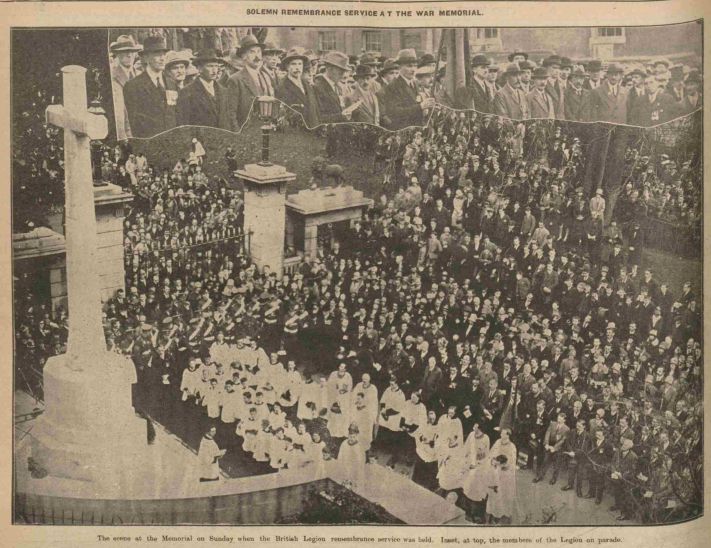

SPONTANEITY

The service, attended by thousands, who stretched to the limits of Queen Square, Queen’s Place, and a hundred yards along Gravel Walk and the Royal Avenue, lasted only 27 minutes, but 27 minutes packed with tense feeling, so tense in fact, that a number of women, overcome by the occasion, fainted. Lest we forget! Can we ever forget? Bath mourns as acutely as she ever did. Time can soften grief, but it cannot stifle it. “Annulling youth’s brief years,” death took away their all. No wonder, then, the spontaneity of the vast concourse who came and, more impressive even than that, of the service itself.

There were no shouted directions, no broadcast instructions. The service just went on of its own volition. Every one took part. There was no hitch, no unwanted intrusion. The service proceeded by itself, because the people felt it. They were expressing themselves, their innermost feelings. The effect was unforgettable.

THE BEREAVED

The setting for so memorable a happening was fitting. In the place of honour in front of the memorial were the flesh and blood of those commemorated. Mothers wore their sons’ medals, widows wore those of their husbands; here and there a child had daddy’s. Such a one was a little boy who clung to the rails on the other side of the road – a baby then, a boy now, a man to-morrow. He watched with an intentness that was inescapable; chords in his youthful nature seemed to be touched, even if he were but a child.

There were the Deputy Mayor for the occasion, Major-General Elliott Bradshaw, who has served his country well in war and in peace; Lord Allenby in Field Marshal’s uniform, the Marquis of Bath as Lord Lieutenant, the Bishop of Bath & Wells, with Canon Alcock as his chaplain, the Archdeacon of Bath, the Rev. F. G. Gatehouse (who represented the Free Churches), and the members of the City Council in their robes.

THE “OLD CONTEMPTIBLES”

Flanking these and others were the various military units, valiant for their services in the Great War. The Red Cross, the “Old Contemptibles,” with breasts covered with medals, and carrying aloft a standard, a remnant of an indomitable army. In this “season of mists and mellow fruitfulness” the sun threw a pathway of gold across the enclosure.

Everyone in their places, the service began. Without preliminary, the huge congregation, led by the band of the 4th Somersets, under Bandmaster Tobin, sang with wonderful reverence the hymn, “O God, our help in ages past.” It was an outlet for pent-up emotions. The hymn rose and fell in impressive cadences. The voices rolled away in the distance in one sonorous unity of sound.

HOMELY PRAYERS

The prayers said by the Archdeacon were brief, homely and eminently appropriate.

To the Rev. F. G. Gatehouse, of New King Street, as representing the Free Churches fell the duty of reading hte lesson, which he did in fine resonant tones. It was chosen from the 22nd chapter of the Revelations.

“And they shall see His face and His name shall be in their foreheads. And there shall be no night there, and they need no cndle, neither light of the sun; for the Lord God giveth them light, and they shall reign for ever and ever.”

“...and the leaves of the trees were for the healing of the nations.”

THE UNVEILING

Then came the formal handing over from the Committee to the City. Major G. D. Lock, addressing the Deputy Mayor, said: “I have the honour to ask you to accept on behalf of the City of Bath this Memorial, which has been erected by 5,000 citizens in memory of those who made the great sacrifice in the Great War.” Then General Bradshaw in answer said: “I have been requested by the Mayor to act as Deputy Mayor to-day at this ceremony, and, on behalf of the City of Bath, I gratefully accept this War Memorial as a sacred trust for all time.” Finally he asked the unveiler to unveil it.

Lord Allenby, stepping forward, a fine figure of a soldier and a man, pulled the cords which brought down the draping flags which surrounded the cross itself and the entablature. Then he gravely saluted the Honoured Dead. The dedication followed. For this solemn purpose the Bishop, with the Archdeacon and his Chaplain ascended the steps into the Shrine itself, and with hand uplifted announced “To the Glory of God and in Memory of the Men of this City who fell in the Great War I dedicate this Memorial in the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.” At this point Sir Harry Hatt stepped forward with a wreath of poppies and rosemary “for remembrance” and placed it beneath the cross as a token of love and recollection on behalf of all the bereaved, and bearing the inscription “In Loving Memory from the Relatives of All the dear ones Who Died that we might live. ‘How bright those glorious Spirits shine’.

A TOUCHING INCIDENT

Sir Harry Hatt, who during his capital Mayoralty lost his two gallant officer sons was a fitting representative of all the rest who mourn. His wreath in position, Sir Harry bowed his head a moment, and everyone must have been touched by his grief and the grief of all who have lost loved ones, too. Those Flanders poppies stood out against their setting of green and their background of greystone – like the shining examples of the men who have gone, and yet abide.

Then Lord Allenby spoke. He is like all great soldiers, a man of action rather than of speech, yet in matter of fact language he “traced the epitaph of glory fled” and in a clarion call to those who remain urged us to carry on the great work for mankind which those Valiant Heroes began and could not finish. A manly utterance, a noble utterance. As he had saluted the dead, so at the conclusion he saluted the living.

Voices were afterwards uplifted in the second hymn “Jesu, Lover of my soul,” sung to that grand old tune Aberystwyth. It brought comforting grace, the soothing of reposefulness. It rang our clear, sad, solemn, and yet full of a wistful hopefulness in the still autumn air. Thousands joined in it. Its music must have reached the skies. The benediction pronounced by the Bishop, followed, and as his last words died away there rang out from within the Park itself the plaintive strains of the Last Post, sounded by the buglers of the 4th Somersets.

TWO MINUTES’ SILENCE

The two minutes’ Silence hushed the thousands to an unnatural quiet. Here the spontaneity was very marked. An absolute hush fell. Only the twittering of the birds could be heard and an occasional stifled sob. With bowed heads, the vast assembly stood mute and wrapped intheir most sacred thoughts. The little boy on the wall wearing his father’s medals closed his eyes. Some did not attempt to keep the tears back.

The Reveille broke the tension which was almost too much to endure, and then came the placing of wreaths by official bodies. Behind them, the first private individual to do so, came an old lady, humble of station, yet she had suffered like the rest, and in her hand she carried a few flowers – all she had – and these she deposited side by side of the fine and costly tributes already placed there, and they shone with a glory all their own. Perhaps she had watered them with her tears. But be sure they found as great a favour in His sight as any. The National Anthem closed the memorable and striking occasion, which was at once a rededication and a revowal of our hope.

THE MILITARY PARADE

[Which followed Lord Allenby’s address and the civic procession, details of both of which are reproduced in detail in the original article].

The 4th Batt. Somerset L.I. were drawn up across the roadway at the entrance gates to the Royal Victoria Park, the band and buglers being on the bank on the right-hand side of the entrance. From the lower side of the Memorial and across the road to the corner of Queen’s Place were detachments from the North Somerset Yeomanry, the 204th (Wessex) Field Co. R.E., the Regimental Old Comrades’ Association, the St. John Ambulance Brigade, V.A.D., and British Red Cross, while across the roadway of Queen’s place were representatives of the Queen Mary Army Auxiliary Corps, the British Legion and Pensions Hospital.

Note the women wearing their menfolk's medals .

After the ceremony, Lord Allenby had tea at the Legion headquarters and then motored to Bristol to catch the 5.15 to Paddington.

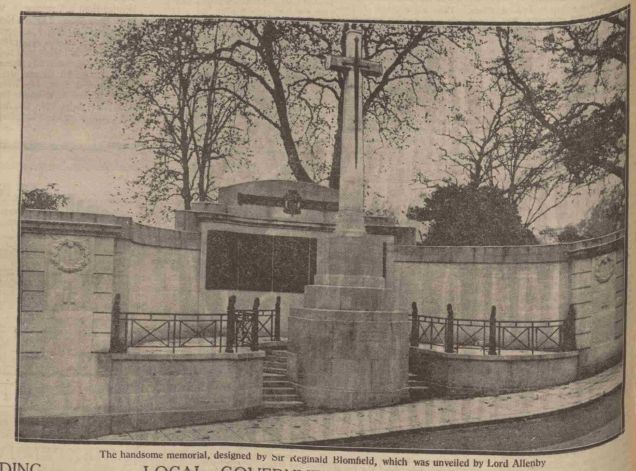

A BEAUTIFUL MEMORIAL

“Stay and Remember”

The memorial takes the form of the Cross of Sacrifice as designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield, R.A., who himself attended this afternoon’s ceremony. This form of cross, it is interesting to note, was selected for erection in the British war cemeteries overseas. On each side of the cross, which is on a massive pedestal, is a short flight of steps, which give access to the curved portion of the memorial, the inner platforms being fronted with ornamental railings. Above the bronze tablets is a bronze scroll, with the City Arms in the centre, Bearing in relief: “They died for us. Men of Bath who fell in the Great War 1914-1918.”

On the outside of the stone cross, and conforming to its shape, is a large bronze sword. The pedestal has carved on its front in sunken gilt letters: “Stay and remember those who died for you.” It is in every respect a beautiful memorial.

The War Memorial Committee are to be congratulated on the consummation of their efforts. Few outside their own ranks know the vast amount of work they put in and the multifarious difficulties with which they were confronted, but they successfully overcame them all. The Mayor (Alderman Cedric Chivers) has acted as President of the Committee, Major G.D. Lock as Chairman, Mr. H.H. Stallard as hon. treasurer, and Mr Gordon Dudley as hon. secretary.

Days later, the first Armistice Day service took place at the memorial.

The Bath War Memorial has since received additional tablets to commemorate those who lost their lives in WW2, both as servicemen and as civilians (e.g. in the deadly air raids on Bath of April 1942), and also in other conflicts since.

For some time, a website created by a mr Terry Morgan gave basic details of all the men listed on the Bath war memorial, but this has disapeared since Virgin Media stopped hosting websites in the summer of 2016. Hopefully, it will be possible to have this information available again before long!?